Waters in the New England region of the U.S. may soon be the location for a first-of-its-kind field trial to test a technique called ocean alkalinity enhancement (OAE), that researchers say could someday become a pivotal tool in the fight against climate change.

But, fishermen are concerned the experiment could further disrupt an ecosystem already contending with the effects of offshore wind energy development and climate change.

“I first heard about it at the June [New England Fishery Management] Council meeting,” said Jerry Leeman, a former Maine fisherman who now heads the New England Fishermen’s Stewardship Association. “Everybody in that room, all 40 of us, our jaws dropped. It caught a lot of people off guard. My phone started blowing up with every fisherman you could imagine, from Cutler, Maine, all the way down the mid-Atlantic, asking questions.”

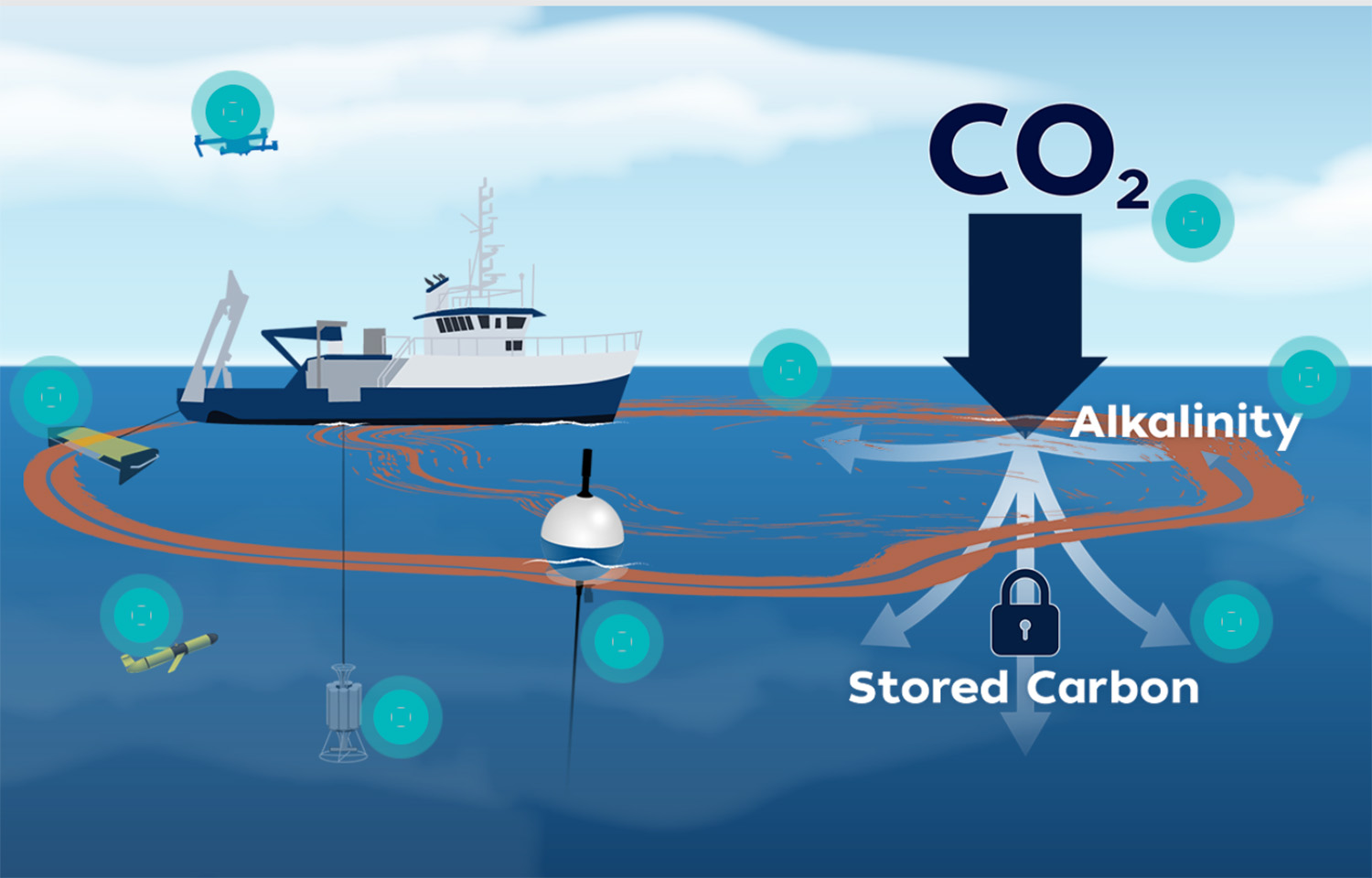

The planned LOC-NESS project, short for “Locking Ocean Carbon in the Northeast Shelf and Slope,” is led by researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). Its purpose is to monitor the dispersal patterns and environmental impacts of a controlled release of sodium hydroxide into surface waters. As one of 17 projects supported by a USD 23.4 million (EUR 20.9 million) investment by the National Oceanographic Partnership Program, LOC-NESS is part of a new wave of research designed to help identify ocean-based carbon removal, or “negative emissions,” techniques that are safe, effective, and affordable.

In addition to OAE, other proposed ocean-based carbon removal techniques include the cultivation and sinking of kelp biomass and the fertilization of nutrient-poor areas of the ocean to boost phytoplankton growth. In theory, all of these techniques could enhance the ocean’s natural ability to draw carbon dioxide molecules out of the atmosphere and store them in the ocean for decades or centuries. If implemented at scale, they could hypothetically slow the rise of global temperatures.

However, these techniques are beset by significant data gaps related to the measurability of carbon removal, the durability of carbon storage, and possible side effects on local ecosystems and communities. Laboratory studies and modeling have only been able to provide partial answers to these questions so far, prompting leaders in the field to call for the initiation of in-situ pilot projects like the LOC-NESS project.

At a listening session in Point Judith, Rhode Island, the WHOI-based research team linked their planned LOC-NESS project to this larger need for data collection.

"We're responding to a whole suite of scientific consensus that this research needs to get done,” said Adam Subhas, a geochemist leading the project. Recent international and national reports, Subhas said, have “emphasized the need for in-water experiments that take this out of the lab and see if this is a viable solution or not.”

For fishermen at the listening session, however, the scientific merits of the project paled in comparison with their apprehension about local ecological impacts.

“The ocean's not a lab rat,” Point Judith fisherman Chris Brown, who serves as board president of the Seafood Harvesters of America, said, adding he would be asking his organization to oppose the project. “Maybe it’s harmless, maybe it’s not. But, we don’t have a lot of appetite for your curiosity for dumping lye into the ocean."

Lye is the common name for sodium hydroxide, the chemical at the center of the LOC-NESS field trial. It is used in many common commercial applications, WHOI researcher Jennie Rheuban explained. For instance, bakers use it to make soft pretzels, and municipalities use it to adjust the pH of drinking water.

The first phase of the LOC-NESS project would release 6,600 gallons of this substance, which has a chemical abbreviation of NaOH, at a 50 percent concentration into federal waters south of Martha’s Vineyard over 90 minutes, using a vessel’s wake to rapidly mix the solution into the surrounding water. Pending the results of the first trial, a second phase would release 66,000 gallons into Wilkinson’s Basin over three to six hours. The WHOI research team anticipates that the solution will instantly dissociate into sodium (Na+) and hydroxide (OH-) ions, causing a localized increase in pH that will return to safe drinking water limits within minutes and baseline levels within 72 hours.

The EPA is currently considering whether to grant a final permit for the LOC-NESS project under the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA). However, the agency already announced its tentative approval of the project in June after concluding that the short-term environmental impacts of the project appear minor in comparison to the project’s value in expanding scientific understanding of OAE’s potential as a long-term climate solution.

Fishermen at the session apparently found little comfort in these assurances, with some confessing that their reactions to the LOC-NESS project are strongly colored by recent experiences with offshore wind energy development. Participants said they fear that small-scale research projects like LOC-NESS could become a foot in the door that is exploited by commercial interests to unleash private investment in ocean-generated carbon offsets before adequate environmental safeguards can be put in place.

“We are always told that it’s just going to be a little project, to see if it does any damage,” Newport, Rhode Island, lobsterman Lanny Dellinger said to the WHOI research team. “Then, it gets carried away. You guys are only curious. You want to see if this works. Well, it doesn't matter. Some brainchild is going to decide, 'This is the way to go, pedal to the metal,’ and there will be all kinds of damage."

Subhas was quick to differentiate the WHOI research team from commercial interests looking to “make a buck.” In fact, participants on all sides of the conversation seemed to agree on the need for strong environmental oversight and transparency as bulwarks against rampant profiteering as the field of ocean-based carbon removal matures.

“We're trying to do right by the science here,” Subhas said. “What I don't want to see … is this to turn into a huge money-making thing that ends up causing way more harm."

Prior to the listening session, the LOC-NESS team announced through its email list that its planned field trials, originally slated to start in September 2024, will be postponed until the summer of 2025 due to changes in research vessel availability.

Fishermen at the session said that researchers might now use the intervening year to fill knowledge gaps related to the project’s potential impact on commercially and recreationally important fish and invertebrate species. Their appeal echoed requests made by fishing associations and businesses during the EPA’s public comment period earlier this summer and by NOAA Fisheries in its Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) consultation. Those entreaties asked the EPA to require additional laboratory and mesocosm studies on the effects of sodium hydroxide on fish eggs and larvae before allowing field trails to move forward.

Members of the WHOI team said they are eager to learn from fishermen and plan to be as responsive to fishermen’s needs as they can be within the constraints of their available resources and timeline. The listening session was the first of many interactive opportunities that the team hopes to host throughout the region for members of the fishing community. These community engagement activities are purely voluntary, and are not required by any permit or regulatory process.

“I'm hoping that this can be the start of a conversation with you all about what this looks like and what we are going to see moving forward,” Subhas conveyed to fishermen at Wednesday’s listening session. “We're going to be communicating. We want to be upfront with you."

WHOI’s LOC-NESS project is the first initiative to seek a federal permit related to an ocean-based carbon removal research project in the U.S., and it has the potential to set the stage for efforts that may follow. Perhaps even more significantly, the U.S. does not yet have any comprehensive, purpose-built regulatory framework in place to govern ocean-based carbon dioxide removal. Experts like Columbia University’s Romany Webb, a legal scholar who specializes in carbon dioxide removal, said that the next few years may see the introduction of new legislative and regulatory proposals to fill this gap.